Get Real By: Solita Collas-Monsod

The Senate version of the much-vaunted TRAIN (Tax Reform for

Acceleration and Inclusion), Senate Bill No. 1592, was passed this week.

Let me tell you, Reader, and I am joined by highly respected colleagues

in this view, that it leaves much to be desired.

We need this tax reform program because the administration’s platform

is based on a “Build, Build, Build” program to improve the country’s

infrastructure—not only physical (roads, bridges, etc.) but also human

(i.e., to improve the people’s education, skills, training) and even

natural. President Duterte wants to accelerate our pace of development.

The problem lies in the fact that with the current tax structure, the

government cannot finance it. We have a structure that is old, creaky

and full of loopholes. For example, our excise taxes on fuel haven’t

been changed in 20 years. In 1998, fuel excises constituted around 50

percent of fuel prices—the same as other countries. Now they constitute

maybe 10 percent.

For loopholes, how about our value-added taxes (VAT)? Sure, we have

about the highest VAT rate in the region, but there are so many

exemptions. Sen. Panfilo Lacson pointed this out when he said that the

Philippines’ exemptions were more than those of Thailand, Malaysia,

Vietnam and Indonesia put together (PH=143, T+I+M+V=111).

So, to raise the funds to finance our Philippine Development Plan and

to make up for the needed reductions in personal income tax, we need to

streamline and update our tax structure. That’s what the Department of

Finance set out to do. Finance Secretary Sonny Dominguez was reported to

have said that his proposed increase in the fuel excises would bring in

P177 billion, and that removing the VAT exemptions would bring in P166

billion.

Hence the tax reform—to pay for the physical infrastructure and human

capital development (P40 billion for free college tuition). And there’s

universal healthcare, estimated at around P50 billion, etc. And then we

have to make sure that the poor are not further marginalized.

So what happened? Well, for one, all the foregoing—the country’s

needs—took a back seat to the individual needs of our senators. Someone

monitoring the discussions told me that this was the first time (in

three Congresses) that the senators were so open about what they wanted

for themselves.

They even had pet names for themselves, like “Papa Bear” (Gordon, I

am told), “Mama Bear” (Villar supposedly), and “Ice Queen” (allegedly

Legarda). And if their individual needs or interests clashed with the

needs of tax reform, guess who won?

Example: Sen. Sonny Angara’s interests led him to include ecozones

(not just direct exporters) among those with VAT zero rating, thus

adding to, rather than reducing, the exemptions. And anything that would

affect real estate was given wide berth, to accommodate Mama Bear.

When the senators realized that their pet insertions had reduced the

expected revenues of the tax reform, they scrambled to add more

revenue-raising provisions. And so you had a doubling of the documentary

stamps tax, a doubling of the minerals excise tax, a tax on coal 10 to

30 times its present rate. Is that good? No. No one bothered to check

what the overall impact would be. As a colleague described it: all

whimsical or arbitrary, all without the benefit of complete staff work.

The senators did arrange for the cash transfers to the poor for three

years: The additional revenues from TRAIN would be divided into 60

percent for physical infrastructure, 27 percent for human infrastructure

(including the cash transfers), and 13 percent for the Armed Forces.

However, if the poor are to get the P50.4 billion envisaged (P3,600 a

year x 14 million families—yes, the Senate considers the poor to

comprise 70 percent of our families), revenues from the Senate’s TRAIN

should be at least P187 billion. The latest estimated revenues are about

P120 billion.

Yet, in spite of the need to raise revenues, sin taxes (with complete

supporting studies) were not even considered. Senators Manny Pacquiao

and JV Ejercito presumably were convinced not to pursue this, because

anyway, it will be included in TRAIN II “early” next year. Anybody want

to bet on that? Elections are coming, and taxes and elections do not mix

well.

source: Inquirer

Sunday, December 3, 2017

Thursday, October 5, 2017

Bye bye, Build Build Build?

The Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) has been billed

as the administration’s flagship legislation for achieving sustainable

seven percent growth, generating investments and jobs,and reducing

poverty. If TRAIN is derailed — kiss Build, Build, Build, bye bye.

There is some concern that the Senate version of TRAIN passed two weeks ago, heavily diluted the original tax reform package proposed by the DoF. According to press reports citing the Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council (LEDAC),the likely incremental revenue yield of the Senate bill is only around P55B, around 0.3% of GDP. Compare this to the target revenue yield of the original proposal of the DoF of P157B, (1% of GDP), or even the House version of P134B (0.8% of GDP). Or what the Philippine Development Plan aims: for infrastructure spending to ramp up to 7% of GDP by 2022 from last year’s 3.4%.

Moreover, as stressed by Foundation for Economic Freedom last Sept. 14, “Tax reform is particularly important in the face of new spending mandated by Congress — free irrigation, free tuition in SUCS (state universities and colleges), escalating pension benefits of uniformed personnel, and increases in SSS (Social Security System) pensions unmatched by increases in contribution.” The incremental yield of the Senate bill barely covers the estimated first year cost of the free tuition law. And with inordinate amount of earmarks to boot.

If government pursues its programmed five-year infrastructure spending on top of all these Congress-mandated new ones without the matching new revenues, the country courts an explosive public debt buildup.More immediately, we put at risk another “BBB” — the Philippines “investment grade” credit rating. Keeping an investment grade rating is essential. It makes the country attractive to investors and keeps borrowing cost low for both government and the private sector, including small businesses and first time homebuyers.

The major sources of dilution in the Senate version according to experts are —

1. Plugging VAT exemption loopholes. The Senate version only lifted 36 VAT exemptions from the 70 lines in the DoF bill. Moreover the Senate bill gives new exemptions to ecozones.

2. Fuel taxes, auto excise taxes were watered down and made more complicated.

3. The option to pay 8% on gross for all self-employed, in lieu of income taxes at the top marginal rate of 35%.

On the VAT exemption loopholes, the consequence of having too many holes is a VAT yield of only 4.3% of GDP, around the same as Thailand’s, even when their VAT rate is only 7%.

My favorite example of a bad tax exemption — seniors citizens’ VAT exemption on top of a legally mandated 20% discount. This is exceedingly regressive as government subsidizes in direct proportion to amount of spending, and gives minimal benefits to the needy elderly poor. Its other objectionable feature from a tax policy standpoint is the high administration cost, and its window for abuse by opportunistic taxpayers/establishments and crooked tax collectors. The DoF originally proposed to limit this exemption to medicines, and to instead provide annual cash transfers similar to the Pantawid Pamilya for the elderly poor.

There are dozens of similarly unmeritorious exemptions like this that the DoF tried to wholesale correct in their version of the bill. (At the same time, the DoF has shown flexibility in recognizing truly deserving cases. For example, with the BPO industry, one of two key drivers of the economy in terms of direct and indirect employment, foreign exchange, and economic activity. Both House and Senate versions provide for a formula that allows the industry to continue to significantly contribute to the economy in the face of anti-outsourcing rhetoric in the US, concerns of foreign clients over security concerns like Marawi/ISIS, and the accelerating negative impact of technological disruption/Artificial Intelligence.)

On the oil taxes,while the three versions converge to same rate after year 3, the Action for Economic Reforms has argued that the back loading, especially in the Senate version impacts on the ability of government to fund the compensating cash transfers needed in the early years.(Though one can also argue that timing actually dovetails with the J curve ramp up in infra spending, given government’s absorptive capacity/execution limitations.) There is also the risk to the planned revenue increase for the outer years due to the 2019 election.

Finally, on item 3 — the revenue losses from the overly generous eight percent gross option for the self-employed (initially only for smaller establishments), has been estimated by the DoF/AER to be upwards of P20 billion. While its Senate sponsors have argued that there will be more taxpayers who will pay with the much lower rate, I doubt that tax evaders now paying zero will find virtue just because the tax rate is lower. Especially since, surfacing previously hidden income stream may expose them to charges of evasion on past income.

Moreover, this measure severely fails the test of horizontal equity — as salaried people, especially at the higher tax brackets, will be subject to three to four times the burden of the self-employed.

In order to make up for the huge gap in revenue yield, the Senate version introduced new items that were originally programmed for future packages by the DoF. They have thus not been subject to full consultations. Some quick notes on these new items:

1) Increase in taxes on dividends and on FCDU dollar interest income to 20%.

Premature and piece meal in light of a comprehensive review being undertaken by a team of experts commissioned by the DoF/ADB for reform of capital income taxation (interest, dividends, capital gains) across institutions and financial instruments. The objectives of this capital income tax reform (package 4) include greater neutrality, fairness, simplicity, and efficiency — to be supportive of government’s capital market development efforts.

2) Coal tax dubbed a carbon tax.

The Senate bill proposed doubling the coal tax from the current P10 per ton. While even this higher level seems modest compared to what is being pushed by alternative fuel interests,this tax should have been left for fuller study under the DoF’s package 5, taxation of products with negative social externalities (which also includes tobacco and alcohol).

Advocates have argued for a much heavier tax on coal based on coal’s higher per unit contribution to global Co2 vs. alternative fuels. They fail to consider that the Philippine Co2 footprint is just 1% of world total,the lowest in ASEAN. Moreover, the renewable energy component of our power mix at 35%, is way above global average — thanks to forward looking investments done over decades in efficient hydro and geothermal plants.

The question we need to ask in levying higher taxes on coal is — given the country’s aim to promote manufacturing investments and job creation, can we afford to further add to our high electricity costs? Such have been made higher recently by compounding feed in tariffs subsidies for wind and solar.

3) Cosmetic surgery (or cosmetic products) tax. This and other similar small yielding tax measures are just administrative burdens.

One is tempted to say, purely cosmetic. But nonetheless valid considerations in Philippine politics, especially bearing in mind 2019 midterm elections. I trust that the bicam and Congress as a whole will find the right balance between short term politics and our country’s long term development imperatives.

Romeo L. Bernardo is a board director of the Institute for Development and Econometric Analysis. He was undersecretary of Finance during the Corazon Aquino and Fidel Ramos administrations.

There is some concern that the Senate version of TRAIN passed two weeks ago, heavily diluted the original tax reform package proposed by the DoF. According to press reports citing the Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council (LEDAC),the likely incremental revenue yield of the Senate bill is only around P55B, around 0.3% of GDP. Compare this to the target revenue yield of the original proposal of the DoF of P157B, (1% of GDP), or even the House version of P134B (0.8% of GDP). Or what the Philippine Development Plan aims: for infrastructure spending to ramp up to 7% of GDP by 2022 from last year’s 3.4%.

Moreover, as stressed by Foundation for Economic Freedom last Sept. 14, “Tax reform is particularly important in the face of new spending mandated by Congress — free irrigation, free tuition in SUCS (state universities and colleges), escalating pension benefits of uniformed personnel, and increases in SSS (Social Security System) pensions unmatched by increases in contribution.” The incremental yield of the Senate bill barely covers the estimated first year cost of the free tuition law. And with inordinate amount of earmarks to boot.

If government pursues its programmed five-year infrastructure spending on top of all these Congress-mandated new ones without the matching new revenues, the country courts an explosive public debt buildup.More immediately, we put at risk another “BBB” — the Philippines “investment grade” credit rating. Keeping an investment grade rating is essential. It makes the country attractive to investors and keeps borrowing cost low for both government and the private sector, including small businesses and first time homebuyers.

The major sources of dilution in the Senate version according to experts are —

1. Plugging VAT exemption loopholes. The Senate version only lifted 36 VAT exemptions from the 70 lines in the DoF bill. Moreover the Senate bill gives new exemptions to ecozones.

2. Fuel taxes, auto excise taxes were watered down and made more complicated.

3. The option to pay 8% on gross for all self-employed, in lieu of income taxes at the top marginal rate of 35%.

On the VAT exemption loopholes, the consequence of having too many holes is a VAT yield of only 4.3% of GDP, around the same as Thailand’s, even when their VAT rate is only 7%.

My favorite example of a bad tax exemption — seniors citizens’ VAT exemption on top of a legally mandated 20% discount. This is exceedingly regressive as government subsidizes in direct proportion to amount of spending, and gives minimal benefits to the needy elderly poor. Its other objectionable feature from a tax policy standpoint is the high administration cost, and its window for abuse by opportunistic taxpayers/establishments and crooked tax collectors. The DoF originally proposed to limit this exemption to medicines, and to instead provide annual cash transfers similar to the Pantawid Pamilya for the elderly poor.

There are dozens of similarly unmeritorious exemptions like this that the DoF tried to wholesale correct in their version of the bill. (At the same time, the DoF has shown flexibility in recognizing truly deserving cases. For example, with the BPO industry, one of two key drivers of the economy in terms of direct and indirect employment, foreign exchange, and economic activity. Both House and Senate versions provide for a formula that allows the industry to continue to significantly contribute to the economy in the face of anti-outsourcing rhetoric in the US, concerns of foreign clients over security concerns like Marawi/ISIS, and the accelerating negative impact of technological disruption/Artificial Intelligence.)

On the oil taxes,while the three versions converge to same rate after year 3, the Action for Economic Reforms has argued that the back loading, especially in the Senate version impacts on the ability of government to fund the compensating cash transfers needed in the early years.(Though one can also argue that timing actually dovetails with the J curve ramp up in infra spending, given government’s absorptive capacity/execution limitations.) There is also the risk to the planned revenue increase for the outer years due to the 2019 election.

Finally, on item 3 — the revenue losses from the overly generous eight percent gross option for the self-employed (initially only for smaller establishments), has been estimated by the DoF/AER to be upwards of P20 billion. While its Senate sponsors have argued that there will be more taxpayers who will pay with the much lower rate, I doubt that tax evaders now paying zero will find virtue just because the tax rate is lower. Especially since, surfacing previously hidden income stream may expose them to charges of evasion on past income.

Moreover, this measure severely fails the test of horizontal equity — as salaried people, especially at the higher tax brackets, will be subject to three to four times the burden of the self-employed.

In order to make up for the huge gap in revenue yield, the Senate version introduced new items that were originally programmed for future packages by the DoF. They have thus not been subject to full consultations. Some quick notes on these new items:

1) Increase in taxes on dividends and on FCDU dollar interest income to 20%.

Premature and piece meal in light of a comprehensive review being undertaken by a team of experts commissioned by the DoF/ADB for reform of capital income taxation (interest, dividends, capital gains) across institutions and financial instruments. The objectives of this capital income tax reform (package 4) include greater neutrality, fairness, simplicity, and efficiency — to be supportive of government’s capital market development efforts.

2) Coal tax dubbed a carbon tax.

The Senate bill proposed doubling the coal tax from the current P10 per ton. While even this higher level seems modest compared to what is being pushed by alternative fuel interests,this tax should have been left for fuller study under the DoF’s package 5, taxation of products with negative social externalities (which also includes tobacco and alcohol).

Advocates have argued for a much heavier tax on coal based on coal’s higher per unit contribution to global Co2 vs. alternative fuels. They fail to consider that the Philippine Co2 footprint is just 1% of world total,the lowest in ASEAN. Moreover, the renewable energy component of our power mix at 35%, is way above global average — thanks to forward looking investments done over decades in efficient hydro and geothermal plants.

The question we need to ask in levying higher taxes on coal is — given the country’s aim to promote manufacturing investments and job creation, can we afford to further add to our high electricity costs? Such have been made higher recently by compounding feed in tariffs subsidies for wind and solar.

3) Cosmetic surgery (or cosmetic products) tax. This and other similar small yielding tax measures are just administrative burdens.

One is tempted to say, purely cosmetic. But nonetheless valid considerations in Philippine politics, especially bearing in mind 2019 midterm elections. I trust that the bicam and Congress as a whole will find the right balance between short term politics and our country’s long term development imperatives.

Romeo L. Bernardo is a board director of the Institute for Development and Econometric Analysis. He was undersecretary of Finance during the Corazon Aquino and Fidel Ramos administrations.

Introspective By Romeo L. Bernardo

romeo.lopez.bernardo@gmail.com

Thursday, August 10, 2017

Tax holiday for inclusive business models

Package two of the country’s tax reform initiatives will take a look at how to rationalize fiscal incentives. Certain factors that are being considered by our Finance department include the selection of industries to be promoted, the actual performance of registered entities vis-a-vis targets, and the period for availing of the incentives. It will be interesting to see how the government will continue to incentivize activities that result in positive social impact and inclusive growth. One of these activities currently qualified for fiscal incentives is the corporate Inclusive Business (IB) model.

IB is a private sector or business approach specifically

directed at low-income communities or people who live at the Base of the

Pyramid (BoP). A company adopting this approach customizes its business

model to include low-income communities in its value chain as

customers, suppliers, distributors, retailers, or employees. IBs provide

more access to basic goods and services, and create opportunities for

employment and livelihood to the marginalized sector in a sustainable,

scalable, and commercially viable manner.

While it seems philanthropic, IBs are actually profitable investments. They also provide opportunities for large-scale businesses to realize reasonable profits from markets with significant growth potential, while making a positive social impact like reducing poverty and supporting community development. Hitting two birds with one stone as the old cliché goes.

IBs differ from Corporate Social Responsibility activities in that the latter are not conceptualized with commercial viability and profit in mind. However, both are effective ways of engaging the private sector to collaborate and partner with the low income communities, sharing in the responsibility of the government to bolster growth in all sectors, especially at the BoP.

Recognizing its potential, the Board of Investments (BoI) included IB in the 2014 Investments Priorities Plan (IPP), not as a preferred activity for investment eligible for incentives but as a key strategy for inclusive growth, and as a general policy for encouraging registered enterprises to adopt IB strategies and practices.

In the 2017 IPP, IB models finally got listed as one of the preferred activities. The IPP recognized business activities of medium and large enterprises in the agribusiness and tourism sectors which target micro and small enterprises (MSE) as part of their value chains. IB projects that are eligible for registration may qualify for BoI Pioneer status with entitlement to five years of income tax holiday.

To illustrate an IB model, let’s take an agribusiness enterprise that sources its raw materials (e.g. coffee beans, sugar, or cocoa) from low-income farmers, MSEs, or farmer’s cooperatives.

The enterprise may enter into a contract growing agreement with the farmers and may guarantee the purchase of their produce. It may provide technical assistance (e.g. trainings, seminars) or access to finance (e.g. loans, collateral) and farm inputs.

Further, the IPP enumerates the targets and the timetable for implementation of IB models.

Under the guidelines, within three years of commercial operations, at least 25% of the value of total cost of goods sold of qualified agribusiness enterprises and total cost of goods/services of qualified tourism enterprises must be sourced from registered and/or recognized MSEs (including cooperatives, or any organized entity duly recognized by a government body), as evidenced by a duly notarized contract. Moreover, there must be at least a 20% increase in the average income of individuals engaged from such MSEs from the baseline year to the third year of actual operations.

For qualified agribusiness enterprises, at least 300 farmers, fisherfolk, suppliers, and/or individual beneficiaries must be engaged, of which, at least 30% must be women. On the other hand, at least 25 direct jobs (regular employment) must be generated by qualified tourism enterprises for individuals in the identified database (e.g., DSWD Conditional Cash Transfer Graduates, DAR Agrarian Reform Beneficiaries, NCIP List, PWD, and others) of which, at least 30% must be women.

In addition, the enterprise must exhibit innovation in the business model through: (1) the provision of technical assistance/capacity building to the MSEs, farmers, fisherfolk, or employees that increases productivity and/or quality; or (2) facilitation of access to finance either directly or in partnership with a third party (i.e. provision of collateral by the company, direct lending through a subsidiary or third party-financing disbursed directly to the MSEs, farmers, fisherfolk, or employees or through the company).

Innovation in the business model may also be exhibited by agribusiness enterprises through the provision of inputs and/or technology to MSEs and/or individual farmers and fisherfolk.

Interested enterprises with agribusiness and tourism projects may opt to undertake IB models by submitting their duly notarized IB plans in the required BoI format upon application for registration.

A business strategy that incorporates the marginalized sectors of society may finally serve to break the shackles of poverty. As aptly expressed in the United Nations Report entitled, Creating Value for All: Strategies for Doing Business with the Poor (2008): “Inclusive business models build bridges between business and the poor for mutual benefit. The benefits for business go beyond immediate profits and higher income. For business, they include driving innovations, building markets, and strengthening supply chains. And for the poor, they include access to essential goods and services, higher productivity, sustainable earnings, and greater empowerment.”

With the promise that it holds, there is reason for the government to qualify IB models for fiscal incentives.

The views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Isla Lipana & Co. The content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for specific advice.

Reynaldo E. Maniego III is a manager at the Tax Services Department of Isla Lipana & Co., the Philippine member firm of the PwC network.

+63 (2) 845-2728

reynaldo.e.maniego.iii@ph.pwc.com

While it seems philanthropic, IBs are actually profitable investments. They also provide opportunities for large-scale businesses to realize reasonable profits from markets with significant growth potential, while making a positive social impact like reducing poverty and supporting community development. Hitting two birds with one stone as the old cliché goes.

IBs differ from Corporate Social Responsibility activities in that the latter are not conceptualized with commercial viability and profit in mind. However, both are effective ways of engaging the private sector to collaborate and partner with the low income communities, sharing in the responsibility of the government to bolster growth in all sectors, especially at the BoP.

Recognizing its potential, the Board of Investments (BoI) included IB in the 2014 Investments Priorities Plan (IPP), not as a preferred activity for investment eligible for incentives but as a key strategy for inclusive growth, and as a general policy for encouraging registered enterprises to adopt IB strategies and practices.

In the 2017 IPP, IB models finally got listed as one of the preferred activities. The IPP recognized business activities of medium and large enterprises in the agribusiness and tourism sectors which target micro and small enterprises (MSE) as part of their value chains. IB projects that are eligible for registration may qualify for BoI Pioneer status with entitlement to five years of income tax holiday.

To illustrate an IB model, let’s take an agribusiness enterprise that sources its raw materials (e.g. coffee beans, sugar, or cocoa) from low-income farmers, MSEs, or farmer’s cooperatives.

The enterprise may enter into a contract growing agreement with the farmers and may guarantee the purchase of their produce. It may provide technical assistance (e.g. trainings, seminars) or access to finance (e.g. loans, collateral) and farm inputs.

Further, the IPP enumerates the targets and the timetable for implementation of IB models.

Under the guidelines, within three years of commercial operations, at least 25% of the value of total cost of goods sold of qualified agribusiness enterprises and total cost of goods/services of qualified tourism enterprises must be sourced from registered and/or recognized MSEs (including cooperatives, or any organized entity duly recognized by a government body), as evidenced by a duly notarized contract. Moreover, there must be at least a 20% increase in the average income of individuals engaged from such MSEs from the baseline year to the third year of actual operations.

For qualified agribusiness enterprises, at least 300 farmers, fisherfolk, suppliers, and/or individual beneficiaries must be engaged, of which, at least 30% must be women. On the other hand, at least 25 direct jobs (regular employment) must be generated by qualified tourism enterprises for individuals in the identified database (e.g., DSWD Conditional Cash Transfer Graduates, DAR Agrarian Reform Beneficiaries, NCIP List, PWD, and others) of which, at least 30% must be women.

In addition, the enterprise must exhibit innovation in the business model through: (1) the provision of technical assistance/capacity building to the MSEs, farmers, fisherfolk, or employees that increases productivity and/or quality; or (2) facilitation of access to finance either directly or in partnership with a third party (i.e. provision of collateral by the company, direct lending through a subsidiary or third party-financing disbursed directly to the MSEs, farmers, fisherfolk, or employees or through the company).

Innovation in the business model may also be exhibited by agribusiness enterprises through the provision of inputs and/or technology to MSEs and/or individual farmers and fisherfolk.

Interested enterprises with agribusiness and tourism projects may opt to undertake IB models by submitting their duly notarized IB plans in the required BoI format upon application for registration.

A business strategy that incorporates the marginalized sectors of society may finally serve to break the shackles of poverty. As aptly expressed in the United Nations Report entitled, Creating Value for All: Strategies for Doing Business with the Poor (2008): “Inclusive business models build bridges between business and the poor for mutual benefit. The benefits for business go beyond immediate profits and higher income. For business, they include driving innovations, building markets, and strengthening supply chains. And for the poor, they include access to essential goods and services, higher productivity, sustainable earnings, and greater empowerment.”

With the promise that it holds, there is reason for the government to qualify IB models for fiscal incentives.

The views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Isla Lipana & Co. The content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for specific advice.

Reynaldo E. Maniego III is a manager at the Tax Services Department of Isla Lipana & Co., the Philippine member firm of the PwC network.

+63 (2) 845-2728

reynaldo.e.maniego.iii@ph.pwc.com

Thursday, August 3, 2017

Waves of waivers

Some of the important lessons in life we

learn from unpleasant experiences. Learning from the mistakes of our

past keeps us from repeating them. Wisdom comes from accepting errors

and exercising better judgment in the future.

The above statements hold true even in tax collection. In the past, the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) lost assessment cases due to the issue of waivers on the statute of limitations for the assessment of deficiency taxes. It may have learned its lesson the hard way, but the Bureau has implemented improved measures stemming from its experience.

In a 2004 case (G.R. 162852 dated Dec. 16, 2004), the Supreme Court ruled that a waiver must strictly conform to the requirements set forth under the rules; otherwise, the waiver is invalid. At that time, the prevailing rule on the proper execution of a waiver of the statute of limitations was Revenue Memorandum Order (RMO) No. 20-1990 and Revenue Delegation Authority Order No. 5-2001.

In a subsequent case (G.R. No. 212825 dated Dec. 7, 2015), the Supreme Court provided an exception to the general rule on validity of waivers. The crux of the issue pertained to the issuance of defective waivers, arising from the fault of both the taxpayer and the BIR. The waivers were said to be executed by the taxpayer’s accountant without a notarized board authority to sign in behalf of the company. On the other hand, the BIR was considered to be careless in performing its functions when it did not ensure that the waiver was duly accomplished and signed by an authorized representative, among others.

In that case, the Supreme Court tolerated the BIR’s slip-ups for equitable reasons. The validity of the waiver in favor of the state was then upheld on the strength of the time-honored principle that taxes are the lifeblood of the government. In its decision, the Court said the BIR’s right to collect taxes should not be jeopardized merely because of the mistakes and lapses of its officers, especially in cases where the taxpayer was obviously in bad faith when it voluntarily executed the waivers and subsequently insisted on their invalidity by raising the very same defects it caused. Thus, the taxpayer was estopped from questioning the validity of the waivers.

As for the erring BIR officials, the Court suggested enforcing administrative liabilities for their failure to properly comply with the procedures.

In a more recent decision (G.R. No. 213943 dated March 22, 2017), the Supreme Court ruled that the three-year period to assess was not extended because all the waivers executed by the taxpayer were considered defective. What is significant to note is that the waivers were considered defective because the BIR failed to provide the third copies to the office accepting the waivers and these copies were merely attached to the docket of the case. Also, the revenue official who accepted the third waiver was not authorized to do so. In this case, the defects were solely due to the fault of the BIR.

While the BIR argued that the taxpayer was estopped from questioning the validity of the waivers, the Courts clarified that the BIR cannot shift the blame to the taxpayer for the defective waivers. The BIR cannot easily invoke the doctrine of estoppel to cover its failure to comply with the requirements for valid issuance of waivers. Having caused the defects, the BIR must bear the consequences. Considering that the waivers are defective, the assessment was considered issued beyond the three-year prescriptive period, and thus, void. Contrary to the 2015 case, the Court ruled in favor of the taxpayer here because it played no part in the waivers’ defects.

With the issuance of a new RMO last year, the question is -- Can taxpayers apply the above decisions of the Supreme Court for issues on waivers today?

On April 18, 2016, the BIR issued RMO No. 14-2016 which laid down new guidelines on the execution of waivers. According to the new RMO, compliance with the prescribed form is not mandatory. A taxpayer’s failure to follow the forms would not invalidate the executed waiver, for as long as (1) it is executed before the expiration period, and the date of execution is specifically provided in the waiver; (2) the waiver is signed by the taxpayer or duly appointed representative/responsible official; and (3) the expiry date of the period agreed upon to assess/collect the tax after the three-year period is indicated.

In addition, the new RMO provides that the taxpayer is charged with the burden of ensuring that the waivers are validly executed. The taxpayer must submit the duly executed waiver to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue or to the authorized revenue official (e.g., concerned revenue district officer or group supervisor as designated in the Letter of Authority or Memorandum of Assignment) who shall then indicate acceptance by signing the waiver. Moreover, the taxpayer must retain a copy of the accepted waivers.

Under the new RMO which seems to favor the BIR, it appears that upon execution of the waiver, taxpayers can no longer challenge its validity.

Thus, while there is a level of comfort in the decision of the Court that taxpayers should not be made to suffer for lapses of the BIR, this will only apply to waivers that have been executed prior to the effectivity of the new RMO. The BIR has learned from past mistakes. Here’s to hoping that taxpayers have learned from their own.

The views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Isla Lipana & Co. The content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for specific advice.

Maria Jonas Yap is a Manager at the Tax Services Department of Isla Lipana & Co., the Philippine member firm of the PwC network.

+63 (2) 845-2728

maria.jonas.s.yap@ph.pwc.com

source: Businessworld

The above statements hold true even in tax collection. In the past, the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) lost assessment cases due to the issue of waivers on the statute of limitations for the assessment of deficiency taxes. It may have learned its lesson the hard way, but the Bureau has implemented improved measures stemming from its experience.

In a 2004 case (G.R. 162852 dated Dec. 16, 2004), the Supreme Court ruled that a waiver must strictly conform to the requirements set forth under the rules; otherwise, the waiver is invalid. At that time, the prevailing rule on the proper execution of a waiver of the statute of limitations was Revenue Memorandum Order (RMO) No. 20-1990 and Revenue Delegation Authority Order No. 5-2001.

In a subsequent case (G.R. No. 212825 dated Dec. 7, 2015), the Supreme Court provided an exception to the general rule on validity of waivers. The crux of the issue pertained to the issuance of defective waivers, arising from the fault of both the taxpayer and the BIR. The waivers were said to be executed by the taxpayer’s accountant without a notarized board authority to sign in behalf of the company. On the other hand, the BIR was considered to be careless in performing its functions when it did not ensure that the waiver was duly accomplished and signed by an authorized representative, among others.

In that case, the Supreme Court tolerated the BIR’s slip-ups for equitable reasons. The validity of the waiver in favor of the state was then upheld on the strength of the time-honored principle that taxes are the lifeblood of the government. In its decision, the Court said the BIR’s right to collect taxes should not be jeopardized merely because of the mistakes and lapses of its officers, especially in cases where the taxpayer was obviously in bad faith when it voluntarily executed the waivers and subsequently insisted on their invalidity by raising the very same defects it caused. Thus, the taxpayer was estopped from questioning the validity of the waivers.

As for the erring BIR officials, the Court suggested enforcing administrative liabilities for their failure to properly comply with the procedures.

In a more recent decision (G.R. No. 213943 dated March 22, 2017), the Supreme Court ruled that the three-year period to assess was not extended because all the waivers executed by the taxpayer were considered defective. What is significant to note is that the waivers were considered defective because the BIR failed to provide the third copies to the office accepting the waivers and these copies were merely attached to the docket of the case. Also, the revenue official who accepted the third waiver was not authorized to do so. In this case, the defects were solely due to the fault of the BIR.

While the BIR argued that the taxpayer was estopped from questioning the validity of the waivers, the Courts clarified that the BIR cannot shift the blame to the taxpayer for the defective waivers. The BIR cannot easily invoke the doctrine of estoppel to cover its failure to comply with the requirements for valid issuance of waivers. Having caused the defects, the BIR must bear the consequences. Considering that the waivers are defective, the assessment was considered issued beyond the three-year prescriptive period, and thus, void. Contrary to the 2015 case, the Court ruled in favor of the taxpayer here because it played no part in the waivers’ defects.

With the issuance of a new RMO last year, the question is -- Can taxpayers apply the above decisions of the Supreme Court for issues on waivers today?

On April 18, 2016, the BIR issued RMO No. 14-2016 which laid down new guidelines on the execution of waivers. According to the new RMO, compliance with the prescribed form is not mandatory. A taxpayer’s failure to follow the forms would not invalidate the executed waiver, for as long as (1) it is executed before the expiration period, and the date of execution is specifically provided in the waiver; (2) the waiver is signed by the taxpayer or duly appointed representative/responsible official; and (3) the expiry date of the period agreed upon to assess/collect the tax after the three-year period is indicated.

In addition, the new RMO provides that the taxpayer is charged with the burden of ensuring that the waivers are validly executed. The taxpayer must submit the duly executed waiver to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue or to the authorized revenue official (e.g., concerned revenue district officer or group supervisor as designated in the Letter of Authority or Memorandum of Assignment) who shall then indicate acceptance by signing the waiver. Moreover, the taxpayer must retain a copy of the accepted waivers.

Under the new RMO which seems to favor the BIR, it appears that upon execution of the waiver, taxpayers can no longer challenge its validity.

Thus, while there is a level of comfort in the decision of the Court that taxpayers should not be made to suffer for lapses of the BIR, this will only apply to waivers that have been executed prior to the effectivity of the new RMO. The BIR has learned from past mistakes. Here’s to hoping that taxpayers have learned from their own.

The views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Isla Lipana & Co. The content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for specific advice.

Maria Jonas Yap is a Manager at the Tax Services Department of Isla Lipana & Co., the Philippine member firm of the PwC network.

+63 (2) 845-2728

maria.jonas.s.yap@ph.pwc.com

source: Businessworld

Another look at the tax-exempt status of charitable institutions

Tax exemptions are often met with

reservations and must withstand the strict scrutiny of revenue

collectors. After all, taxes are the driving fuel that propels all

programs and activities of the state. Absolving persons from their tax

liabilities means reducing public funds and restraining the government

from actualizing its goals.

Nevertheless, the legislative groundwork covering the tax exemption of religious and charitable institutions has long been established, even as early as the Commonwealth period. The rationale for the exemption springs from the benevolent neutrality approach premised on the ground that religious and charitable institutions are not engaged in profit-seeking undertakings; whatever gains derived by the organization redounds to charity. Hence, Section 30(E) of the National Internal Revenue Code (or simply, the Tax Code) is specifically couched to incorporate the rationale in these words: a non-stock corporation or association organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, athletic, or cultural purposes, or for the rehabilitation of veterans, wherein no part of its net income or asset shall belong to or inure to the benefit of any member, organizer, officer or any specific person shall be exempt from income tax.

In a recent decision (CTA Case No. 8912 dated July 25, 2017), the Court of Tax Appeals (CTA) emphasized that while our Tax Code provides exemptions for certain non-stock corporations from income tax, this incentive is not absolute. It reiterated that in order to enjoy immunity from taxation, the following requirements for exemption must continually be satisfied by the taxpayer: (a) The taxpayer must be a non-stock corporation or association; (b) Organized exclusively for charitable purposes; (c) Operated exclusively for such purposes; and (d) No part of its net income or asset shall belong to or inure to the benefit of any member, organizer, officer or any specific person.

In the foregoing case, the CTA ruled in favor of the BIR, declaring that while there was no sufficient evidence to prove that any income or asset inured to the benefit of any member or officer of the institution, the 10% preferential tax rate applicable to proprietary hospitals which are nonprofit (under Section 27(B) of the Tax Code) should be imposed since the taxpayer was not operated “exclusively” in charitable purposes. Although not barred from engaging in activities conducted for profit, any income the hospital derives from profit-oriented activities should not escape the reach of taxation. Thus, an organization with both non-profit and profit-generating activities may still enjoy its tax exempt status but only on income from not-for-profit activities. Any income generated from activities conducted for profit shall strictly be subject to income tax.

As basis, the CTA also cited previous cases (G.R. Nos. 195909 and 195960 dated September 26, 2012) where the Supreme Court extensively discussed the application of Section 30(E) of the Tax Code, as amended, and upheld the same decision.

For taxpayers, an important takeaway from this case is that in order to enjoy immunity from taxation, all of the requirements for the same must continually be satisfied by the taxpayer. Thus, being a non-stock and non-profit charitable institution does not automatically exempt an institution from paying taxes.

Generally, just relying on the specific tax-exemption provision of charitable institutions from our Tax Code, a non-stock, non-profit corporation is exempt from paying income taxes at first glance. In some instances, organizations tend to overlook the succeeding provision clearly stating that the exemption only applies to income from non-profit activities. Through this case, the CTA reiterated the prevailing tax position in the Philippines that income from profit-generating activity is taxable, regardless of the disposition of the income earned from such activities. Nonetheless, while this may be the case, an organization may still, at the same time, remain tax-exempt on income from its actual charitable activities. Therefore, it may be deduced that at the end of the day, the determining factor for taxability lies in whether an activity is for profit or not.

To be exempt from tax, the challenge is for charitable and religious organizations to have a better appreciation of the rationale behind their tax-exempt status. As a rule, taxation is the overarching principle and exemption is the exception; as such, the burden of proof rests upon the party claiming exemption to prove that it is, in fact, covered by the exemption so claimed.

The views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Isla Lipana & Co. The content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for specific advice.

Nadine E. Chan is a manager at the Tax Services Department of Isla Lipana & Co., the Philippine member firm of the PwC network.

+63 (2) 845-2728

nadine.e.chan@ph.pwc.com

source: Businessworld

Nevertheless, the legislative groundwork covering the tax exemption of religious and charitable institutions has long been established, even as early as the Commonwealth period. The rationale for the exemption springs from the benevolent neutrality approach premised on the ground that religious and charitable institutions are not engaged in profit-seeking undertakings; whatever gains derived by the organization redounds to charity. Hence, Section 30(E) of the National Internal Revenue Code (or simply, the Tax Code) is specifically couched to incorporate the rationale in these words: a non-stock corporation or association organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, athletic, or cultural purposes, or for the rehabilitation of veterans, wherein no part of its net income or asset shall belong to or inure to the benefit of any member, organizer, officer or any specific person shall be exempt from income tax.

In a recent decision (CTA Case No. 8912 dated July 25, 2017), the Court of Tax Appeals (CTA) emphasized that while our Tax Code provides exemptions for certain non-stock corporations from income tax, this incentive is not absolute. It reiterated that in order to enjoy immunity from taxation, the following requirements for exemption must continually be satisfied by the taxpayer: (a) The taxpayer must be a non-stock corporation or association; (b) Organized exclusively for charitable purposes; (c) Operated exclusively for such purposes; and (d) No part of its net income or asset shall belong to or inure to the benefit of any member, organizer, officer or any specific person.

In the foregoing case, the CTA ruled in favor of the BIR, declaring that while there was no sufficient evidence to prove that any income or asset inured to the benefit of any member or officer of the institution, the 10% preferential tax rate applicable to proprietary hospitals which are nonprofit (under Section 27(B) of the Tax Code) should be imposed since the taxpayer was not operated “exclusively” in charitable purposes. Although not barred from engaging in activities conducted for profit, any income the hospital derives from profit-oriented activities should not escape the reach of taxation. Thus, an organization with both non-profit and profit-generating activities may still enjoy its tax exempt status but only on income from not-for-profit activities. Any income generated from activities conducted for profit shall strictly be subject to income tax.

As basis, the CTA also cited previous cases (G.R. Nos. 195909 and 195960 dated September 26, 2012) where the Supreme Court extensively discussed the application of Section 30(E) of the Tax Code, as amended, and upheld the same decision.

For taxpayers, an important takeaway from this case is that in order to enjoy immunity from taxation, all of the requirements for the same must continually be satisfied by the taxpayer. Thus, being a non-stock and non-profit charitable institution does not automatically exempt an institution from paying taxes.

Generally, just relying on the specific tax-exemption provision of charitable institutions from our Tax Code, a non-stock, non-profit corporation is exempt from paying income taxes at first glance. In some instances, organizations tend to overlook the succeeding provision clearly stating that the exemption only applies to income from non-profit activities. Through this case, the CTA reiterated the prevailing tax position in the Philippines that income from profit-generating activity is taxable, regardless of the disposition of the income earned from such activities. Nonetheless, while this may be the case, an organization may still, at the same time, remain tax-exempt on income from its actual charitable activities. Therefore, it may be deduced that at the end of the day, the determining factor for taxability lies in whether an activity is for profit or not.

To be exempt from tax, the challenge is for charitable and religious organizations to have a better appreciation of the rationale behind their tax-exempt status. As a rule, taxation is the overarching principle and exemption is the exception; as such, the burden of proof rests upon the party claiming exemption to prove that it is, in fact, covered by the exemption so claimed.

The views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Isla Lipana & Co. The content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for specific advice.

Nadine E. Chan is a manager at the Tax Services Department of Isla Lipana & Co., the Philippine member firm of the PwC network.

+63 (2) 845-2728

nadine.e.chan@ph.pwc.com

source: Businessworld

Saturday, July 29, 2017

Get Real: Breaking down the tax reform package

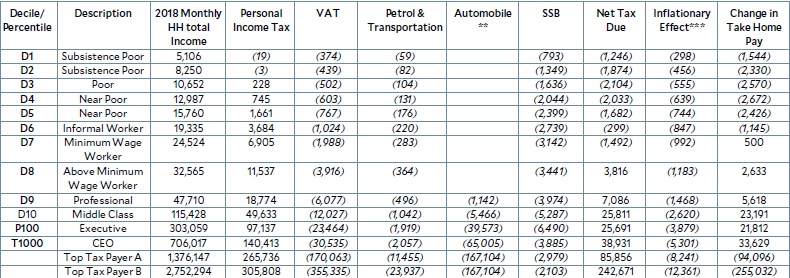

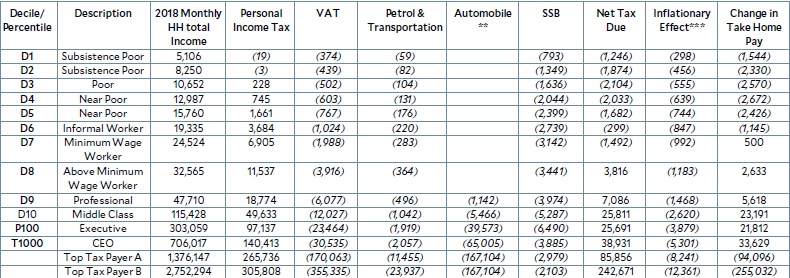

This table, from the Department of Finance, shows its estimates of

the combined impact of the “TARA sa TRAIN” (Tax Administration Reform

Act, Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion) on Filipino households

(hh).

The first column breaks down the households by decile (definition: each of 10 equal groups into which a population can be divided according to the distribution of values of a particular variable, which in this case is household income). Thus, you have the column listing from D1 to D10. The highest income decile (D10) is further broken down into the top 1 percent (P100), and even further into the top 0.1 percent (P1,000). This further subdivision is done so we can see what the tax reform does to this elite class.

The second column describes the characteristics of each of the deciles. Note that the bottom 50 percent of income earners are either “Subsistence Poor,” “Poor” or “Near Poor.” Note that the “Minimum Wage Worker” comes in the seventh decile, and the highest (tenth) income decile is only where the “Middle Class” begins.

That decile is further broken down into “Executive,” those who belong to the top 1 percent, and still further into the top one-tenth of one percent are labeled “CEO.”

Now we come to the third column, which shows the 2018 monthly hh total income by decile. The DOF assumes that each hh has two income earners. The next seven columns give the impact of each of the tax measures in the tax reform package plus the effect of inflation.

The first column breaks down the households by decile (definition: each of 10 equal groups into which a population can be divided according to the distribution of values of a particular variable, which in this case is household income). Thus, you have the column listing from D1 to D10. The highest income decile (D10) is further broken down into the top 1 percent (P100), and even further into the top 0.1 percent (P1,000). This further subdivision is done so we can see what the tax reform does to this elite class.

The second column describes the characteristics of each of the deciles. Note that the bottom 50 percent of income earners are either “Subsistence Poor,” “Poor” or “Near Poor.” Note that the “Minimum Wage Worker” comes in the seventh decile, and the highest (tenth) income decile is only where the “Middle Class” begins.

That decile is further broken down into “Executive,” those who belong to the top 1 percent, and still further into the top one-tenth of one percent are labeled “CEO.”

Now we come to the third column, which shows the 2018 monthly hh total income by decile. The DOF assumes that each hh has two income earners. The next seven columns give the impact of each of the tax measures in the tax reform package plus the effect of inflation.

The

last column summarizes the final impact: the resulting change in

take-home pay. Visually, without even looking at the details, the reader

can see that the bottom 60 percent of income earners are negatively

impacted by the package (the figures are in italics, and are

parenthesized) as well as the top 0.1 percent. Those are the DOF

estimates.

To make up for the minuses, there is a complicated and not yet worked

out system of transfers that add up to P3,000 a year for the first five

deciles and P1,500 for the next two (up to the seventh decile). BUT:

This is relief that lasts only four years. WHY ONLY FOUR YEARS? No one

who has critiqued my stand has answered.

Source: DOF staff estimates using the preliminary Family Income and Expenditure Survey- Labor Force Survey 2015

Notes: Each household has about two income earners

*Total household income includes compensation income, income from entrepreneurial activities (i.e. businesses) and other sources of income (i.e. cash transfers)

**Automobile excise tax impact was computed using 2016 prices, assuming 5 years of amortization

***The inflationary effect was computed as a function of income, marginal propensity to consume (MPC), and estimates on the price effect of the increased oil excise on the price of food

source: Philippine Daily Inquirer By: Solita Collas-Monsod

Source: DOF staff estimates using the preliminary Family Income and Expenditure Survey- Labor Force Survey 2015

Notes: Each household has about two income earners

*Total household income includes compensation income, income from entrepreneurial activities (i.e. businesses) and other sources of income (i.e. cash transfers)

**Automobile excise tax impact was computed using 2016 prices, assuming 5 years of amortization

***The inflationary effect was computed as a function of income, marginal propensity to consume (MPC), and estimates on the price effect of the increased oil excise on the price of food

source: Philippine Daily Inquirer By: Solita Collas-Monsod

Wednesday, July 19, 2017

What the legislature grants, it can take away

While queuing for more than an hour just to

catch a ride home, I noticed commuters in front of me giggling while

staring at their smartphones with earphones on. I subtly leaned in to

find out what was stirring their interest. On the screen, I saw the

familiar faces of Korean actors of a prime time soap opera. I realized

that the benefit of foreign telenovelas among Filipinos is that it helps

to keep them calm and entertained, especially city commuters who endure

hours of standing in line.

With the robust expansion of foreign influences into mainstream media as seen in drama series, K-pop songs and matinee idols (i.e., boy bands), we also see the enhancement of foreign relations between the Philippines, South Korea and the global community at large.

On the economic side, the Philippine government has incessantly endeavored to introduce measures that will increase foreign investment such as providing various fiscal and non-fiscal incentives to foreign investors. One example of these incentives is that specifically provided to regional operating headquarters (ROHQs).

As defined, an ROHQ is a resident foreign business entity which is allowed to derive income in the Philippines by performing qualifying services to its affiliates, subsidiaries or branches in the Philippines, in the Asia-Pacific region and in other foreign markets. Its operations are limited in the sense that it is merely allowed to perform the qualifying services enumerated in the Omnibus Investments Code of 1987, and only for its affiliates. Violation of these rules may result in the revocation of the ROHQ’s license or registration, and effectively, its tax exemptions and incentives.

WHAT EXACTLY ARE THE INCENTIVES PROVIDED BY OUR GOVERNMENT TO THESE ROHQS?

Generally, resident foreign corporations are subject to the 30% corporate income tax. However, as provided in the Tax Code, an ROHQ is liable to income tax at the special rate of 10% based on its taxable income. In addition, an ROHQ is also exempted from the payment of all kinds of local taxes, fees, or charges imposed by the local government, except real property tax on land improvements and equipment. Likewise, it is entitled to a tax and duty-free importation of equipment and materials used for training and conferences.

Moreover, several incentives are also given to expatriate employees of an ROHQ. These include the grant of a multiple entry visa for the expatriate employee including his spouse and unmarried children below the age of 21, tax and duty-free importation of personal and household effects, and travel tax exemption. Most importantly, a preferential tax rate of 15% applies on the salaries, annuities, and all other compensation of expatriates occupying managerial and technical positions exclusively working for the ROHQ and earning a gross annual taxable compensation of at least P975,000. The same treatment applies to Filipinos employed and occupying the same position as those aliens employed by the ROHQ.

Given the huge tax savings and various non-pecuniary benefits profusely provided by the Philippine government, many foreign corporations opted to establish their ROHQs in the Philippines resulting in a boost to foreign investment. This further translated to a rise in job opportunities for highly skilled workers, enticement for highly desirable employees, and a reduction in the risk of brain drain, among others.

A significant change in the incentives provided to ROHQs is being proposed in the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) Bill passed by the House on May 31. Section 7 of the TRAIN Bill amends Section 25 of the National Internal Revenue Code of 1997. Specifically, the Bill deletes the 15% preferential tax rate provided to ROHQ employees occupying managerial and technical positions.

WHAT DOES THE REMOVAL OF THIS PREFERENTIAL TAX RATE MEAN FOR ROHQ EMPLOYEES?

Evidently, the ROHQ employees’ taxable income will then be subject to the normal graduated income tax rates of 0% to 35% applicable to all employees, as proposed by the TRAIN Bill. Those previously enjoying the preferential income tax rate of 15%, given the gross annual income of at least P975,000, will most likely qualify for the 30% to 35% income tax rates. The effective tax rate would, of course, be lower than 30% to 35%, but it would definitely be more than the current 15% rate. Consequently, this would result in reduced take-home pay for such employees if there is no augmentation in their gross compensation.

It is also worth noting that the TRAIN Bill is just the first part of the Tax Reform Program of the Philippine government. The second package intends to review and amend the income taxes on corporations, among others. Thus, it is possible that the 10% special income tax rate provided to ROHQs may also be amended or totally removed.

Some may argue that these reforms will produce unfavorable outcomes for the Philippine economy. Nonetheless, we must always bear in mind that the power of taxation is solely vested in the legislature. It is only Congress, as delegates of the people, which has the inherent power not only to select the subjects of taxation but to grant incentives and exemptions. Given the power to grant, it also has the inherent power to take away. We just have to trust that this move is consistent with the goal of the Tax Reform Program of achieving “efficiency, equity and simplicity” in our tax system and eventually benefit the entire population in the near future.

The views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Isla Lipana & Co. The firm will not accept any liability arising from the article.

Abigael Demdam is a senior consultant at the Tax Services Department of Isla Lipana & Co., the Philippine member firm of the PwC network. Readers may call +63 (2) 845-2728 or e-mail the author at abigael.demdam@ph.pwc.com for questions or feedback.

source: Businessworld

With the robust expansion of foreign influences into mainstream media as seen in drama series, K-pop songs and matinee idols (i.e., boy bands), we also see the enhancement of foreign relations between the Philippines, South Korea and the global community at large.

On the economic side, the Philippine government has incessantly endeavored to introduce measures that will increase foreign investment such as providing various fiscal and non-fiscal incentives to foreign investors. One example of these incentives is that specifically provided to regional operating headquarters (ROHQs).

As defined, an ROHQ is a resident foreign business entity which is allowed to derive income in the Philippines by performing qualifying services to its affiliates, subsidiaries or branches in the Philippines, in the Asia-Pacific region and in other foreign markets. Its operations are limited in the sense that it is merely allowed to perform the qualifying services enumerated in the Omnibus Investments Code of 1987, and only for its affiliates. Violation of these rules may result in the revocation of the ROHQ’s license or registration, and effectively, its tax exemptions and incentives.

WHAT EXACTLY ARE THE INCENTIVES PROVIDED BY OUR GOVERNMENT TO THESE ROHQS?

Generally, resident foreign corporations are subject to the 30% corporate income tax. However, as provided in the Tax Code, an ROHQ is liable to income tax at the special rate of 10% based on its taxable income. In addition, an ROHQ is also exempted from the payment of all kinds of local taxes, fees, or charges imposed by the local government, except real property tax on land improvements and equipment. Likewise, it is entitled to a tax and duty-free importation of equipment and materials used for training and conferences.

Moreover, several incentives are also given to expatriate employees of an ROHQ. These include the grant of a multiple entry visa for the expatriate employee including his spouse and unmarried children below the age of 21, tax and duty-free importation of personal and household effects, and travel tax exemption. Most importantly, a preferential tax rate of 15% applies on the salaries, annuities, and all other compensation of expatriates occupying managerial and technical positions exclusively working for the ROHQ and earning a gross annual taxable compensation of at least P975,000. The same treatment applies to Filipinos employed and occupying the same position as those aliens employed by the ROHQ.

Given the huge tax savings and various non-pecuniary benefits profusely provided by the Philippine government, many foreign corporations opted to establish their ROHQs in the Philippines resulting in a boost to foreign investment. This further translated to a rise in job opportunities for highly skilled workers, enticement for highly desirable employees, and a reduction in the risk of brain drain, among others.

A significant change in the incentives provided to ROHQs is being proposed in the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) Bill passed by the House on May 31. Section 7 of the TRAIN Bill amends Section 25 of the National Internal Revenue Code of 1997. Specifically, the Bill deletes the 15% preferential tax rate provided to ROHQ employees occupying managerial and technical positions.

WHAT DOES THE REMOVAL OF THIS PREFERENTIAL TAX RATE MEAN FOR ROHQ EMPLOYEES?

Evidently, the ROHQ employees’ taxable income will then be subject to the normal graduated income tax rates of 0% to 35% applicable to all employees, as proposed by the TRAIN Bill. Those previously enjoying the preferential income tax rate of 15%, given the gross annual income of at least P975,000, will most likely qualify for the 30% to 35% income tax rates. The effective tax rate would, of course, be lower than 30% to 35%, but it would definitely be more than the current 15% rate. Consequently, this would result in reduced take-home pay for such employees if there is no augmentation in their gross compensation.

It is also worth noting that the TRAIN Bill is just the first part of the Tax Reform Program of the Philippine government. The second package intends to review and amend the income taxes on corporations, among others. Thus, it is possible that the 10% special income tax rate provided to ROHQs may also be amended or totally removed.

Some may argue that these reforms will produce unfavorable outcomes for the Philippine economy. Nonetheless, we must always bear in mind that the power of taxation is solely vested in the legislature. It is only Congress, as delegates of the people, which has the inherent power not only to select the subjects of taxation but to grant incentives and exemptions. Given the power to grant, it also has the inherent power to take away. We just have to trust that this move is consistent with the goal of the Tax Reform Program of achieving “efficiency, equity and simplicity” in our tax system and eventually benefit the entire population in the near future.

The views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Isla Lipana & Co. The firm will not accept any liability arising from the article.

Abigael Demdam is a senior consultant at the Tax Services Department of Isla Lipana & Co., the Philippine member firm of the PwC network. Readers may call +63 (2) 845-2728 or e-mail the author at abigael.demdam@ph.pwc.com for questions or feedback.

source: Businessworld

Sunday, July 16, 2017

No deal

The tax evasion proceedings against homegrown cigarette manufacturer

Mighty Corp. is proving to be a test case in the Duterte

administration’s campaign to punish corporate offenders.

It has, we heard, already caused a rift between lawmakers and President Duterte’s officials.

Mighty’s offer to settle was finally made public last week by the Department of Finance, which is reviewing the proposal sent to its attached unit, the Bureau of Internal Revenue, which is the lead agency in the cigarette firm’s case.

In a July 10 letter to Internal Revenue Commissioner Caesar R. Dulay, Mighty president Oscar Barrientos indicated that the firm was willing to “settle all such excise and tax issues and respectfully offer as settlement of the company’s shareholders’ and its officers’ liability … the total sum of P25 billion.”

The BIR has filed three tax-evasion cases against Mighty at the Department of Justice for its alleged use of fake tax stamps in order to dodge payment of excise taxes. It estimated the unpaid taxes at P37.88 billion.

It has, we heard, already caused a rift between lawmakers and President Duterte’s officials.

Mighty’s offer to settle was finally made public last week by the Department of Finance, which is reviewing the proposal sent to its attached unit, the Bureau of Internal Revenue, which is the lead agency in the cigarette firm’s case.

In a July 10 letter to Internal Revenue Commissioner Caesar R. Dulay, Mighty president Oscar Barrientos indicated that the firm was willing to “settle all such excise and tax issues and respectfully offer as settlement of the company’s shareholders’ and its officers’ liability … the total sum of P25 billion.”

The BIR has filed three tax-evasion cases against Mighty at the Department of Justice for its alleged use of fake tax stamps in order to dodge payment of excise taxes. It estimated the unpaid taxes at P37.88 billion.

Barrientos

said the settlement sum would be funded by an interim loan from the

unit of Japan Tobacco Inc. (JTI) in the Philippines and the sale by

Mighty and its affiliates of its manufacturing and distribution business

and assets, along with the associated intellectual property rights,

including those owned by the company Wong Chu King Holdings Inc., and

other affiliates to JTI “for a total purchase price of P45 billion,

exclusive of VAT.” In effect, Mighty will cease operations after

concluding its deal with JTI.

Barrientos indicated that Mighty would pay P3.5 billion in deficiency

excise taxes on its cigarette products that are now the subject of the

three tax cases pending at the DOJ. Mighty would also remit P21.5

billion “representing the liabilities of the company and its

shareholders, as well as the company officers for all internal revenue

taxes, including income tax from 2010 to 2016 and the tax period up to

the closing of the proposed transaction with JTI, and all transaction

taxes related to the agreement with JTI.”

He said that the initial payment of P3.5 billion would be paid by Mighty on or before July 20, and that a binding memorandum of agreement in relation to the proposed transaction with JTI would be concluded before that date. The balance is to be paid upon or after the sale of Mighty to JTI.

After all these, Mighty wants the BIR to issue to the company and its shareholders and officers “the relevant certificate of availment of compromise, a final tax assessment for all the company’s excise and other tax issues described above, and relevant tax clearances to the company, its shareholders and officers,” Barrientos said.

Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III is correct to make it clear that any settlement offer by Mighty for its tax deficiencies should be separate from the criminal charges that might be filed in court by the BIR against it. Dominguez’s position that criminal liability should be left out of any settlement with Mighty is the alleged cause of disagreement between the cigarette firm and its backers in Congress on one hand, and the President’s economic team on the other.

Clearing Mighty of criminal liability under the proposed settlement will certainly weaken the government’s resolve to weed out unscrupulous businessmen who have been depriving the people of vital public services through nonpayment of taxes. Settlement with a company that underpaid its taxes without intending to—for example, due to a disparity in valuations—should be agreeable. But this should not be so for a company that deliberately evaded the payment of taxes by resorting to criminal acts like the use of fake tax stamps.

And just as a reminder, Section 263 of the Tax Code states that any person found in possession of locally manufactured articles subject to excise tax, the tax on which has not been paid in accordance with the law, shall be punished with a fine of not less than 10 times the amount of excise tax due, as well as imprisonment.

He said that the initial payment of P3.5 billion would be paid by Mighty on or before July 20, and that a binding memorandum of agreement in relation to the proposed transaction with JTI would be concluded before that date. The balance is to be paid upon or after the sale of Mighty to JTI.

After all these, Mighty wants the BIR to issue to the company and its shareholders and officers “the relevant certificate of availment of compromise, a final tax assessment for all the company’s excise and other tax issues described above, and relevant tax clearances to the company, its shareholders and officers,” Barrientos said.

Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III is correct to make it clear that any settlement offer by Mighty for its tax deficiencies should be separate from the criminal charges that might be filed in court by the BIR against it. Dominguez’s position that criminal liability should be left out of any settlement with Mighty is the alleged cause of disagreement between the cigarette firm and its backers in Congress on one hand, and the President’s economic team on the other.

Clearing Mighty of criminal liability under the proposed settlement will certainly weaken the government’s resolve to weed out unscrupulous businessmen who have been depriving the people of vital public services through nonpayment of taxes. Settlement with a company that underpaid its taxes without intending to—for example, due to a disparity in valuations—should be agreeable. But this should not be so for a company that deliberately evaded the payment of taxes by resorting to criminal acts like the use of fake tax stamps.

And just as a reminder, Section 263 of the Tax Code states that any person found in possession of locally manufactured articles subject to excise tax, the tax on which has not been paid in accordance with the law, shall be punished with a fine of not less than 10 times the amount of excise tax due, as well as imprisonment.

source: Philippine Daily Inquirer

Saturday, July 8, 2017

A Letter Notice cannot substitute for a Letter of Authority

Taxation is the lifeblood of the

government. Through the collected taxes, the government is able to fund

the increasing need of its people for infrastructure, education, health,

etc. The Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) is the Philippine

government’s largest revenue collecting arm. For this year alone, the

Bureau was assigned a P1.8 trillion tax collection target.

Throughout the years, the BIR has implemented various programs to improve its tax collection efforts. In 2003, it issued Revenue Memorandum Order (RMO) Nos. 30-2003 and 42-2003 which provided policies and guidelines to detect tax leaks by matching data from the BIR’s Integrated Tax System (ITS) and data from third party resources. Discrepancies generated through these matchings were used to unearth what could potentially be undeclared sales and/or over-claimed purchases by various taxpayers.

This “no-contact-audit approach” enables the BIR to use computerized matching to compare data from records or various returns filed by a taxpayer against those gathered from its suppliers or customers, and even those reported to other agencies, particularly the Bureau of Customs. Taxpayers with noted discrepancies are then informed of the findings through the issuance of a Letter Notice (LN) by the BIR. Consequently, such taxpayers are given 120 days to reconcile the inconsistencies; otherwise, deficiency taxes will be assessed.

In one of its recent decisions, the Supreme Court (SC) held that the absence of a Letter of Authority (LOA), makes the assessment unauthorized and thus, void. This is despite the prior issuance of an LN. According to the court, the BIR’s failure to issue an LOA constituted a violation of due process and was considered fatal to the tax audit.